Agents Need to Fail Better

A Conversation with Yutori Co-founder and Chief Scientist Dhruv Batra

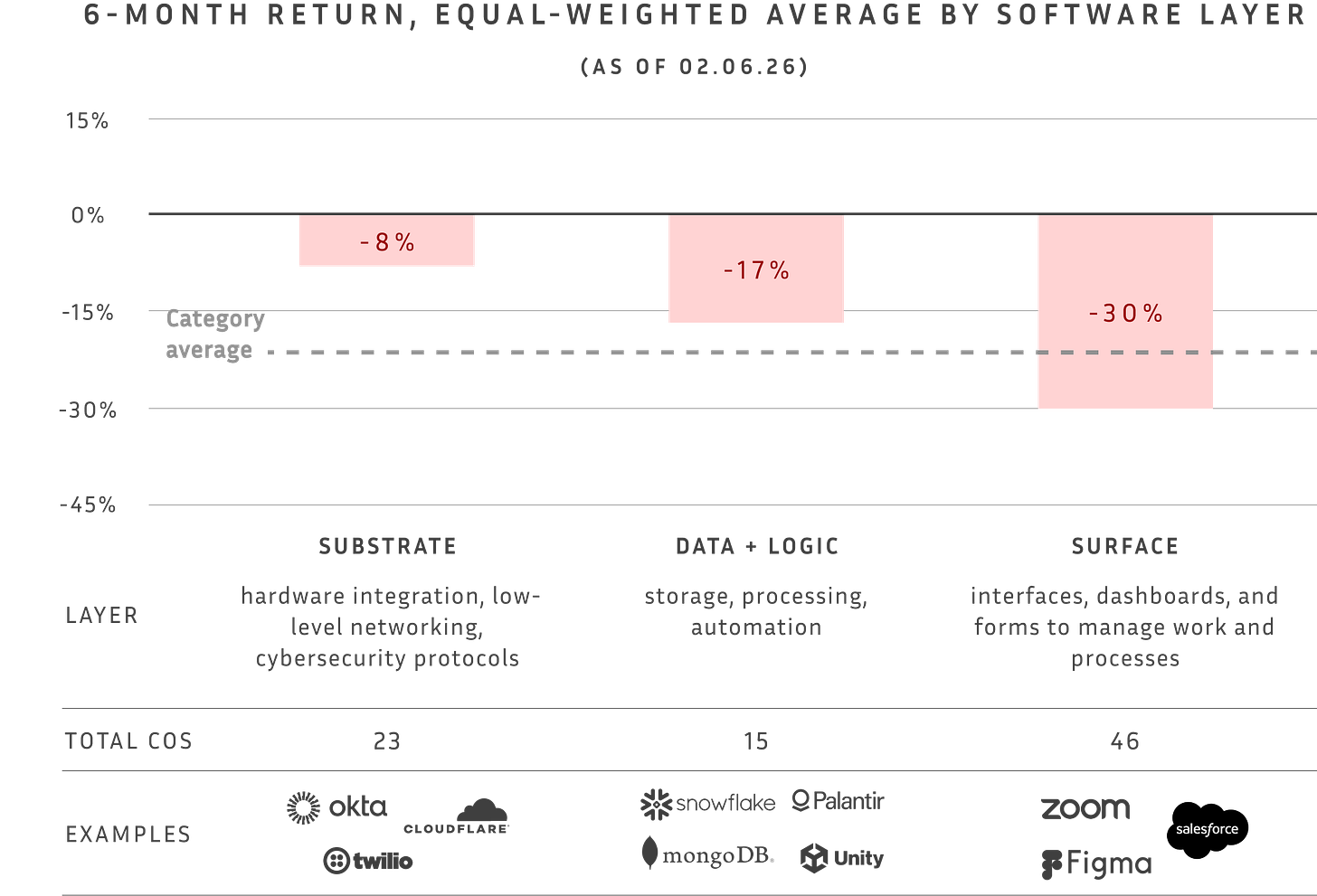

January was a brutal month for software.

Overall, public SaaS is down 15% year-to-date. But the pain isn’t evenly distributed. Companies built around UIs, forms, and human workflows are feeling it the most.

The markets are pricing in a “SaaS-pocalypse.”

Agents, the story goes, will execute workflows on demand, spinning up interfaces and interacting directly with data. In that world, the only enduring value in software are (i) agents – and (ii) the data and infra layers that feed them. Pre-built software applications will become obsolete.

That story assumes agents will work reliably. Right now, most don’t. They’re still brittle. They lose context. They don’t recover well from mistakes.

There’s a branch of computer science called embodied AI1 that offers a different way to think about how agents should be built, and the infrastructure they need to operate effectively.

Embodied AI is built on the insight that intelligence can’t exist in a vacuum. Brains don’t connect directly to their surroundings. They need a body to mediate between raw cognition and the external world. Intelligence, in this view, emerges from continuous-loop interaction between an agent, its physical form, and its environment.

Dhruv Batra is a leader in embodied AI, with a deep understanding of how machines can be built to navigate complex, dynamic environments.

Dhruv was previously a Research Director at Meta’s FAIR (Fundamental AI Research), where he spearheaded the development of Habitat (the fastest 3D simulator for training virtual robots) and the team that built the AI assistant integrated into Meta Ray-Ban SmartGlasses.

Before that, he was an Associate Professor at Georgia Tech, working at the intersection of computer vision, machine learning, natural language processing, and robotics.

Today, Dhruv is co-founder and Chief Scientist at Yutori, a new startup rethinking web agents from the ground up.

Alongside a team of researchers from Meta, Tesla, Palantir, and Google, his bet is that the web should be treated less like a database to parse and reason over, and more like a physical environment – chaotic, visual, dynamic.

I sat down with Dhruv to explore the future of agentic software through the lens of embodied AI – how these agents need to be built and the gaps that remain if these products are to fulfill their promise.

01 | Bits move faster than atoms

EO: You spent a good chunk of your career in embodied AI, teaching machines to perceive and act in real-world environments. Now, you’re focused on web agents that live, at least today, in the digital realm. Tell me about that journey.

DB: I actually started my career in computer vision and machine learning. A decade ago, I co-authored a paper that outlined early methods for chatbots to answer questions about images, which won the Everingham Prize last year for stimulating a new strand of vision and language research.

But five or six years ago, I grew dissatisfied with chatbots. I wanted them to do things in the world. That took me into reinforcement learning, then robotics.

I’m not a roboticist by training. So I earned my credibility, doing things like supervising PhD students in the field and winning a best paper award at a robotics conference.

I don’t see physical robots arriving before digital agents.

Bits move faster than atoms. They’re easier to clone and iterate on. So I took all that learning and started Yutori.

Why did you land on web agents specifically?

Our thesis is that the web is going to fundamentally change. Over the next decade, probably sooner, no human should have to operate a browser. Why click buttons or fill out forms when machines can handle it?

In 2025, we saw real progress with coding agents, but no digital assistants that could automate entire browser workflows. The models weren’t there yet, but we knew it was coming. We saw a window of opportunity.

So where do current web agents fall short? In my experience, Claude’s computer use and OpenAI Operator are getting pretty good.

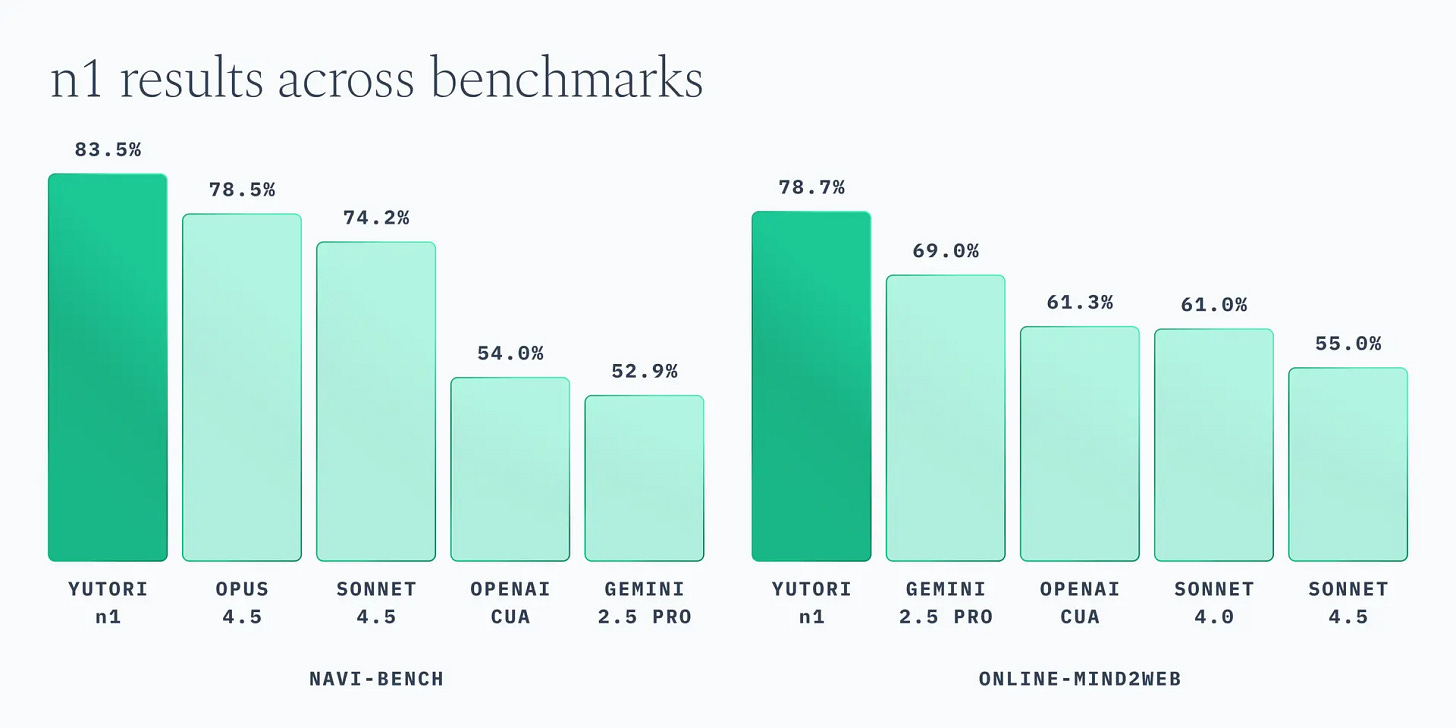

They are improving. But our browser-use model, n1, outperforms Opus 4.5, GPT 5.2, and Gemini 2.5.2 (Gemini 3 computer use benchmarks aren’t out yet, so that comparison isn’t possible.)

Why is our model outperforming? Better perception-action feedback loops3 – something I learned from robotics.

Historically, most AI models were pre-trained on static data – text and images from the web. That’s a good foundation, but it doesn’t teach the model how to act or recover when things go wrong.

This is a known problem in robotics. Mistakes compound. If your robot slips on ice, it’s now in a body configuration it hasn’t been trained on, and things can spiral. And when there’s hardware involved, compounding mistakes are costly. So we train robotic systems to course correct when an action doesn’t produce the expected result.

When we started Yutori, that kind of perception-action feedback data was underrepresented in how most web agents were trained. Without that, agents don’t learn to recover.

So how do you train agents to recover from mistakes, to fail better?

Through post-training – supervised fine-tuning (SFT)4 and reinforcement learning (RL)5 on both synthetic and real websites.

In robotics, you have to choose your training approach depending on the task. For locomotion, RL works well because the physics relevant to the tasks transfer over. An angle is an angle – a robot’s leg should bend the same way in simulation as in the real world.

But for vision-based tasks like picking up objects, camera input is tied to the environment. Every room has different lighting, every surface reflects differently. You can’t simulate all of that, so you rely on human demonstrations that the robot learns to copy.

Web agents don’t have those constraints. The sim-to-real gap6 is small in the digital world, and training on live websites is safe and low risk.

That means we can do SFT based on demonstrations, showing the agent what to do when a button doesn’t load or a page renders incorrectly. And we can do RL on real websites, rewarding successful actions and recovery.

That combination teaches our agents resilience and persistence.

Is there something in your approach – like your multi-agent orchestration – that big companies like Anthropic won’t replicate, because they think differently about how agents should work?

First off, the foundation labs absolutely can deploy these techniques. In AI, there are no secrets that can be kept forever. The question is – will they? They’re fighting so many battles at once. The advantage we have as a startup is focus.

That said, our agents are very specialized for navigating the web.

Our first product, Scouts, is essentially Google Alerts for the AI era. You tell it “let me know when X happens” – a price drop, a reservation opening up, a company announcing a raise – and it monitors for that continuously.

A key design choice we made is that users shouldn’t have to specify sources, to tell the AI where to look. The system needs to search wide and deep on its own, which means training them to integrate with APIs and third party tools across the web.

But here’s the problem – if you give a single agent more than 100 APIs to call from, it starts thrashing.7 It loses track of what it’s doing.

So we use a hierarchical structure. There’s an orchestrator agent, with access to the full user prompt. That orchestrator directs sub-agents, each specialized for different tool categories. For example, we have a sub-agent for social media, one for news sources, and so on. Each manages a smaller context.

Claude Code and Manus have announced something similar. Teams are arriving at the same discovery – without careful context management, performance degrades.

You mentioned the need to train agents to “integrate with APIs across the web.” But most sites don’t have APIs. How do you program your agents to handle this long-tail of the Internet?

Right. Most websites do not have APIs agents can read from.

For those, we found it’s better for our agents to interact with pixels rather than parse the underlying HTML or JavaScript.

We first approached this as a coding problem. Websites are just code, and so we thought the logical approach is for agents to parse the back-end. But we quickly learned that websites are too heterogeneous. They’re programmed in wildly different ways, with hidden hacks on the back-end.

It turns out the best source of truth is what the human actually sees, the pixels.

That’s counterintuitive, since the back-end contains more information than what’s displayed on the screen.

There’s an analog here to Waymo versus Tesla.

Waymo uses cameras, radars, and LiDAR8 to create a rich, 3D map of the environment. Tesla uses cameras only. Tesla’s argument is that vision is sufficient and scales better, since roads were already designed for humans to navigate visually.

We’re taking the Tesla approach. For them, it is largely about being more cost effective. For us, it’s about managing the litany of edge cases that appear across the web.

Parsing the back-end seems like more information, but it creates more problems than it solves. What’s rendered to the screen follows visual conventions that humans expect, and those are far more stable.

In this case, the right representation matters more than the one with the most data.

02 | Context is everything

Can you touch more on persistence? Your agents are designed to run continuously, for months. I imagine that could get unwieldy if not designed well.

Our product Scouts is unique in that it is “always on,” built for proactive monitoring. That comes with trade-offs. If agents are constantly going out into the world, your costs go up. And you can ruin the user experience with too many or repeat notifications.

The agent needs to know whether it’s already told the user about something. That means remembering everything you told the user in the past.

Five or six years ago, you’d solve that problem with embeddings.9 But we saw how fast model capabilities were evolving, and designed around retrieval instead. We write everything we’ve told the user into a file system, and have a custom agent that runs searches against those files.

Models are good enough to now grep and diff10 against previous reports. It’s easier to hand context retrieval over to an LLM rather than trying to architect a vector database.

How do you manage that at scale? If a Scout has been running for a year, that’s a lot of context.

This is genuinely new territory. I’ve had agents running for ten, eleven months. Such long-running, always-on agents have never been built before.

We built our memory architecture in-house. No open-source frameworks.

Model capabilities are improving fast enough that these frameworks end up crippling the product. A key part of our product value boils down to very careful context management.

How do you think about the right way to design a context graph,11 one that scales and that both meets the capabilities of where agentic systems are today, but also will evolve as models improve?

This is something we think about a lot at Yutori.

Today, context windows12 are the main constraint dictating how AI systems get built. For example, a common failure with MCP13 tool calls is if the response is too verbose, it floods the context window and the agent can’t perform its task. Some harnesses14 now write longer responses to a file for later reference, instead of consuming them directly.

But that problem compounds for agents running 24/7 for months.

File systems are the best we have right now – write context to files, let the agent search and summarize as it goes.

The naive view is that context windows will just keep scaling. But biological systems suggest another path.

What do you mean?

I’ll caveat that biological systems are not perfect analogs for agentic systems.

But what I mean is – mammals don’t have infinite context. When they sleep, they’re compressing memory. Distilling the day’s experience, converting System 2 into System 1 thinking.15 There’s a reason beginners in sports are told to get sufficient sleep. They’re converting new techniques into muscle memory.

I don’t think simple scaling of context windows will get us to years of runtime context. We’ll have to conduct new research around distillation and continual learning. It probably looks like new mechanisms for automatically updating model weights, converting accumulated context and experience into more efficient representations.

Unfortunately, I don’t yet know how to build systems that anticipate that solution.

Maybe there’s a startup opportunity somewhere in there.

03 | The fate of the application layer

Today, the market is betting that agents will render the application layer obsolete. When an agent can generate a workflow on demand – pulling in the requisite data, executing the task, building the interface that lets humans read the output – workflow SaaS products like Salesforce or Adobe lose their reason to exist. How do you see the software stack evolving?

I posted a tongue-in-cheek tweet recently where I wrote that maybe coding is just caching for LLM inference.

What I mean is, when you write a software program, you’re really saving down a solution – a codified way to solve a problem. Code is therefore a stored solution. And if intelligence is the ability to solve problems, then, in the AI era, code is just stored intelligence.

Historically, we built generic apps like Salesforce or Fitbit because it was expensive to solve each person’s problem individually. You build one solution and ship it to millions.

But if LLMs make it cheap to read and reason over code, you can generate custom solutions on demand – hyper-personalized apps, built on the fly.

Does that imply we are heading toward the collapse of business and consumer apps?

It’s possible. The models will get good enough. But the tradeoff comes down to two things.

First, efficiency. It’s wasteful to regenerate the same code for millions of people. It’s economically efficient for someone to own the shared layer, shared libraries and components.

Second, design. Not everyone has product taste. Good software encodes good design decisions. That expertise gets packaged into specialized apps – tools that do something well, presented clearly. You can’t generate everything on the fly. Humans still need curation.

Can I offer a third? Network effects. You’ll still want users collaborating across the same plane of data, context, and reusable functions. Complete customization, all the way down the stack, makes that hard.

Yes. Any one user may not have the autonomy, full picture, or authority to take the software in arbitrary directions.

And if that’s the case, it seems like context management – especially shared context management – becomes the next layer of value.

Maybe the “application layer” becomes middleware for agents – something that stitches together system state, builds a context graph for how work gets done, encodes valid operations, and provides a control plane for human oversight.

Not the agent itself, not the data layer. But specialized software that helps agents traverse and collaborate in specific digital environments.

That framing makes sense to me.

04 | AI’s novelty problem

Do you think there will be two categories of agents? One for constrained environments like enterprise software, and one for the open web?

I lean toward no. The open web is the harder problem. If you can handle that, a constrained environment is just a narrower, more specified version. You tell the agent the rules and constraints, and it should be able to adapt.

You see this with coding agents. If you can operate across many different coding environments, specialized ones typically aren’t a problem – as long as they’re represented in the training data.

That caveat – “as long as they’re in the training data” – seems important.

Yes. The AI field has basically decided we don’t need to solve generalization.

What do you mean?

In machine learning, generalization means the system is capable of running inference on information outside the training distribution the AI has been exposed to.

When I taught Intro to Machine Learning, I introduced generalization as the goal of AI systems on day one. The whole point was building systems that could extrapolate beyond their training data.

But as the field commercialized, we moved away from that. We’ve implicitly decided we will just make the training distribution wide enough that everything we will see at inference is something we’ve already seen in training.

Do you think that holds the field back?

Not necessarily. Scaling up has led to commercial success of AI models, which funds investment and progress. But I do wonder about the implications.

If you give up on generalization, can AI ever develop truly novel solutions? Can it solve problems that no human has ever solved before? Because by definition, those solutions won’t show up in the training data.

That seems like it could be a limitation.

I don’t know the answer. It’s possible that wide enough training data effectively gets us there. Maybe we’ll find out soon, it’s an exciting time.

05 | Bots aren’t all bad

Open standards like TCP/IP, HTTP, OAuth were the connective tissue of the old web. They let disparate software systems communicate. We’re now seeing the first agentic standards emerge – MCP for tool access, UCP for commerce. Are there any gaps you still see?

From an advancement of science perspective, I’ve generally been a proponent of building as much in the open – open weights, open standards – as your economic constraints allow.

At Yutori, for example, our n1 model is post-trained from the Qwen16 family of models. I’d love to see more American open weights and open-source models out there.

But one open standard I’d like to see is a permission layer for agents.

In the future, I imagine everyone will have one or several digital assistants that shadow them, with read access to most things and configurable limits on write access – i.e., don’t purchase above this amount, don’t reach out to these people directly.

Today, it’s mostly all-or-nothing. You either give an agent full access or no access. OAuth exists for users, but there’s no equivalent for agents.

What about agent-to-agent coordination? In closed environments, MCP and A2A are making real progress. But when it comes to decentralized or trustless environments like the open web, is there a gap?

Right now, many website owners still operate from the mindset that automated traffic is bad. As a security measure, if they detect automated traffic, they try to block it.

The web needs to get more nuanced. The world is moving toward agents being the primary drivers of digital action. When an agent makes a request, it should be able to declare – here’s who I am, here’s who I’m operating on behalf of, here’s my intent.

There are commercial questions to sort out too. Is the agent paying for access? Or is the website advertising to the agent? But those are secondary.

The first step is a mindset shift. We need to move past the assumption that bots are bad and toward a model where agents can identify themselves and transact legitimately.

06 | The AI-human interface

Right now, users consume the outputs from your web agents through traditional channels like a web browser or email. In 5-10 years, what do you think the human-AI interface will look like?

My perspective on this question is heavily influenced by my time at Meta.

The team I led there was called FAIR Embodied AI. One of my teams built an image question-answering model that shipped on Ray-Ban Meta glasses, in collaboration with the product team.

I think there are a unique set of constraints that point to glasses as the right form factor.

They’re socially acceptable and lightweight. The world is already laid out for humans, so that’s the vantage point you’d want. And the experience I imagine AI should deliver is – a superintelligent assistant, watching me live my life, proactively and discreetly intercepting when you need it. Glasses fit into that.

Of course, there are a lot of ways that can go wrong. Too proactive, and you end up annoying the user. Not careful about privacy, and you end up in nightmarish scenarios; too careful, and you cut off necessary context.

But there is a magical balance great products can strike.

Is there a form factor that you would short?

Earbuds with cameras. I always found those a bit amusing. I never saw that working.

The eyes don’t belong where the ears should be?

Yeah, but also, you know, people have hair that gets in the way. It’s just not going to work.

For all the folks building in AI wearables, remember – people have hair. We’ll leave it with that insight. Thank you Dhruv.

Thanks for having me.

Embodied AI focuses on agents or robots that operate autonomously in physical or simulated environments and that respond to dynamic conditions in real-time. This is distinct from AI systems like LLMs that process static inputs, such as images or text.

Opus 4.5 is the flagship model from Anthropic. GPT 5.2 is the frontier reasoning model from OpenAI. Gemini 2.5 is the multimodal “thinking” model series from Google DeepMind.

Perception-action feedback loops refer to the cycle where an agent observes its environment (perception), takes an action, and then observes the consequences of that action to inform its next move. Early foundation models were trained on static data – screenshots and text – but not on the sequential, interactive data of taking actions and helping the agent learn from their consequences.

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) is a post-training technique where you show the model examples of correct behavior – in this case, examples of successful web navigation – and teach it to imitate that behavior.

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a technique that trains a model through trial and error. The model takes actions, receives feedback on whether they succeeded or failed, and adjusts its behavior accordingly. Unlike SFT, the model learns from its own experience rather than curated examples.

Sim-to-real gap refers to the difference between how an AI system performs in a simulated environment versus the real world. Policies learned in simulation often fail to transfer because simulators don’t perfectly replicate real-world conditions.

Thrashing is a failure mode in agentic systems where the agent spends so much overhead managing tools and context – tracking which tools are available, what’s been tried, what results have or have not come back – that it can’t make progress on the actual task.

LiDAR is a sensing technology used in autonomous vehicles and robotics that uses laser pulses to measure distances and build a 3D map of the surrounding environment.

Embedding is a technique for converting text into numerical vectors that capture semantic meaning, allowing systems to find similar content by comparing vectors (rather than matching exact words). This used to be the standard approach for building memory systems in agents – you’d store past outputs as embeddings in a vector database and retrieve similar ones to check for duplicates.

Grepping and diffing are basic command-line operations for working with text. Grep searches files for specific patterns; diff compares two files and shows the differences. Here, the LLM uses these operations to search past reports and check what’s changed or what information is new.

A context graph is a structured representation of the knowledge an agent needs to operate effectively – the relationships, rules, and logic that define how things work. In enterprise software, this might be the tacit knowledge of how an organization operates (workflow steps, permissions, templates, etc). In a web agent, it might be the history of past actions, user preferences, and tool outputs.

A context window is the amount of text an AI model can process at once, essentially its working memory. Most frontier models today have context windows ranging from 128k to 1 million tokens, roughly equivalent to 100 to 750 pages of text.

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is an open standard developed by Anthropic that allows AI agents to connect to external tools and data sources through a unified interface.

A harness is the wrapper or framework around an agent that controls how the AI operates – managing tool calls, handling responses, and deciding what goes into the model’s context window.

System 1 and System 2 thinking is a framework in psychology for two modes of thinking. System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive, like recognizing a face or catching a ball. System 2 is slow, deliberate, and effortful, like solving a math problem or learning a new skill. With practice, System 2 processes can become System 1. What once required conscious effort becomes instinct.

Qwen is a family of open-weight models developed by Alibaba. “Open-weight” means the model parameters are publicly available, allowing other companies to use Qwen as a base and fine-tune it for specialized applications.